Doctrine of jura regalia in the 1987 Constitution

The discussion below is based on Agcaoili (2006)'s outline in his book on Land Titles and Deeds. Please see citation below. His books are available in find bookstores nationwide.

The 1987 Constitution provides that, except for agricultural lands of the public domain which alone may be alienated, forest or timber, and mineral lands, as well as all other natural resources must remain with the State, the exploration, development and utilization of which shall be subject to its full control and supervision albeit allowing it to enter into co-production, joint venture or production-sharing agreements, or into agreements with foreign-owned corporations involving technical or financial assistance for large-scale exploration, development and utilization.

Although the majority view is that the Constitution adheres to the doctrine of jura regalia, there is a view that this is not the case. Please see Justice Leonen's dissent below.

The present Constitution, like the 1935 and 1973 Constitutions, embodies the principle of State ownership of lands and all other natural resources in Section 2 of Article XII on "National Economy and Patrimony," to wit:

"Section. 2. All lands of the public domain, waters, minerals, coal, petroleum, and other mineral oils, all forces of potential energy, fisheries, forests or timber, wildlife, flora and fauna, and other natural resources are owned by the State. With the exception of agricultural lands, all other natural resources shall not be alienated. The exploration, development and utilization of natural resources shall be under the full control and supervision of the State. The State may directly undertake such activities or it may enter into co-production, joint venture, or production-sharing agreements with Filipino citizens, or corporations or associations at least sixty per centum (60%) of whose capital is owned by such citizens. Such agreements may be for a period not exceeding twenty-five years, renewable for not more than twenty-five years, and under such terms and conditions as may be provided by law. In cases of water rights for irrigation, water supply, fisheries, or industrial uses other than the development of water power, beneficial use may be the measure and limit of the grant."

The first sentence of Section 2 embodies the Regalian doctrine or jura regalia. Introduced by Spain into these Islands, this feudal concept is based on the States power of dominium, which is the capacity of the State to own or acquire property.

In its broad sense, the term jura regalia refers to royal rights, or those rights which the King has by virtue of his prerogatives. In Spanish law, it refers to a right which the sovereign has over anything in which a subject has a right of property or propriedad. These were rights enjoyed during feudal times by the king as the sovereign.

The theory of the feudal system was that title to all lands was originally held by the King, and while the use of lands was granted out to others who were permitted to hold them under certain conditions, the King theoretically retained the title. By fiction of law, the King was regarded as the original proprietor of all lands, and the true and only source of title, and from him all lands were held. The theory of jura regalia was therefore nothing more than a natural fruit of conquest.

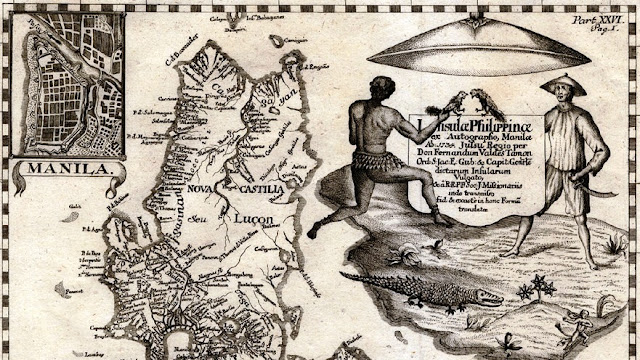

The Philippines having passed to Spain by virtue of discovery and conquest, earlier Spanish decrees declared that all lands were held from the Crown.

The Regalian doctrine extends not only to land but also to all natural wealth that may be found in the bowels of the earth. Spain, in particular, recognized the unique value of natural resources, viewing them, especially minerals, as an abundant source of revenue to finance its wars against other nations. Mining laws during the Spanish regime reflected this perspective. (G.R. No. 127882. January 27, 2004)

Agcaoili (2006) explains that the principle of jure regalia under the present Constitution has its roots in the 1935 Constitution which expressed the overwhelming sentiment in the Convention in favor of the principle of State ownership of natural resources and the adoption of the Regalian doctrine as articulated in Section 1 of Article XIII on "Conservation and Utilization of Natural Resources" as follows:

"Section. 1. All agricultural, timber, and mineral lands of the public domain, waters, minerals, coal, petroleum, and other mineral oils, all-forces of potential energy, and other natural resources of the Philippines belong to the State, and their disposition, exploitation, development, or utilization shall be limited to citizens of the Philippines, or to corporations or associations at least sixty per centum of the capital of which is owned by such citizens, subject to any existing right, grant, lease, or concession at the time of the inauguration of the Government established under this Constitution. Natural resources, with the exception of public agricultural land, shall not be alienated, and no license, concession, or lease for the exploitation, development, or utilization of any of the natural resources shall be granted for a period exceeding twenty-five years, except as to water rights for irrigation, water supply, fisheries, or industrial uses other than the development of water power, in which cases beneficial use may be the measure and the limit of the grant."

Thus, after expressly declaring that all lands of the public domain, waters, minerals, all forces of energy and other natural resources belonged to the State, the Commonwealth absolutely prohibited the alienation of these natural resources. Their disposition, exploitation, development and utilization were further restricted only to Filipino citizens and entities that were 60 percent Filipino-owned.

After the 1935, Constitution, the 1973 Constitution came and reiterated the Regalian doctrine in Section 8, Article XIV on the "National Economy and the Patrimony of the Nation," to wit:

"Section. 8. All lands of the public domain, waters, minerals, coal, petroleum and other mineral oils, all forces of potential energy, fisheries, wildlife, and other natural resources of the Philippines belong to the State. With the exception of agricultural, industrial or commercial, residential, and resettlement lands of the public domain, natural resources shall not be alienated, and no license, concession, or lease for the exploration, development, exploitation, or utilization of any of the natural resources shall be granted for a period exceeding twenty-five years, renewable for not more than twenty-five years, except as to water rights for irrigation, water supply, fisheries, or industrial uses other than the development of water power, in which cases beneficial use may be the measure and the limit of the grant."

The adoption of the concept of jura regalia that all natural resources are owned by the State embodied in the 1935, 1973 and 1987 Constitutions, as well as the recognition of the importance of the country's natural resources, not only for national economic development, but also for its security and national defense, ushered in the adoption of the constitutional policy of "full control and supervision by the State" in the exploration, development and utilization of the country's natural resources. The options open to the State are through direct undertaking or by entering into co-production, joint venture; or production-sharing agreements, or by entering into agreement with foreign-owned corporations for large-scale exploration, development and utilization. (G.R. No. 98332. January 16, 1995)

SOURCE: Agcaoili (2006). Property Registration Decree and Related Laws (Land Titles and Deeds) By Oswaldo D. Agcaoili Formerly Associate Justice, Court of Appeals. ISBN 10: 971-23-4501-7. ISBN 13: 978-971-23-4501-2. Rex Book Store. https://www.rexestore.com/law-library-essentials/279-property-registration-decree-and-related-laws.html

CASE: Generally, under the concept of jura regalia, private title to land must be traced to some grant, express or implied, from the Spanish Crown or its successors, the American Colonial government, and thereafter, the Philippine Republic. The belief that the Spanish Crown is the origin of all land titles in the Philippines has persisted because title to land must emanate from some source for it cannot issue forth from nowhere.

In its broad sense, the term jura regalia refers to royal rights, or those rights which the King has by virtue of his prerogatives. In Spanish law, it refers to a right which the sovereign has over anything in which a subject has a right of property or propriedad. These were rights enjoyed during feudal times by the king as the sovereign.

The theory of the feudal system was that title to all lands was originally held by the King, and while the use of lands was granted out to others who were permitted to hold them under certain conditions, the King theoretically retained the title. By fiction of law, the King was regarded as the original proprietor of all lands, and the true and only source of title, and from him all lands were held. The theory of jura regalia was therefore nothing more than a natural fruit of conquest.

The Regalian theory, however, does not negate native title to lands held in private ownership since time immemorial. In the landmark case of Cario vs. Insular Government theUnited States Supreme Court, reversing the decision of the pre-war Philippine Supreme Court, made the following pronouncement:

x x x Every presumption is and ought to be taken against the Government in a case like the present. It might, perhaps, be proper and sufficient to say that when, as far back as testimony or memory goes, the land has been held by individuals under a claim of private ownership, it will be presumed to have been held in the same way from before the Spanish conquest, and never to have been public land. xxx.

The above ruling institutionalized the recognition of the existence of native title to land, or ownership of land by Filipinos by virtue of possession under a claim of ownership since time immemorial and independent of any grant from the Spanish Crown, as an exception to the theory of jura regalia.

In Cario, an Igorot by the name of Mateo Cario applied for registration in his name of an ancestral land located in Benguet. The applicant established that he and his ancestors had lived on the land, had cultivated it, and had used it as far they could remember. He also proved that they had all been recognized as owners, the land having been passed on by inheritance according to native custom. However, neither he nor his ancestors had any document of title from the Spanish Crown. The government opposed the application for registration, invoking the theory of jura regalia. On appeal, the United States Supreme Court held that the applicant was entitled to the registration of his native title to their ancestral land.

Cario was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1909, at a time when decisions of the U.S. Court were binding as precedent in our jurisdiction. We applied the Cario doctrine in the 1946 case of Oh Cho vs. Director of Lands, where we stated that [a]ll lands that were not acquired from the Government either by purchase or by grant, belong to the public domain, but [a]n exception to the rule would be any land that should have been in the possession of an occupant and of his predecessors in interest since time immemorial, for such possession would justify the presumption that the land had never been part of the public domain or that it had been private property even before the Spanish conquest. (Justice Kapunan's separate opinion in G.R. No. 135385. December 6, 2000)

LEONEN'S DISSENT: Respectfully, I disagree with the ponencia's statement that "the State owns all lands that are not clearly within private ownership." This statement is an offshoot of the idea that our Constitution embraces the Regalian Doctrine as the most basic principle in our policies involving lands.

The Regalian Doctrine has not been incorporated in our Constitution. Pertinent portion of the Constitution provides:

SEC. 2. All lands of the public domain, waters, minerals, coal, petroleum, and other mineral oils, all forces of potential energy, fisheries, forests or timber, wildlife, flora and fauna, and other natural resources are owned by the State[.]

Thus, there is no basis for the presumption that all lands belong to the state. The Constitution limits state ownership of lands to "lands of the public domain[. ]" Lands that are in private possession in the concept of an owner since time immemorial are considered never to have been public. They were never owned by the state.

In Cariño v. Insular Government:

The [Organic Act of July 1, 1902] made a bill of rights, embodying the safeguards of the Constitution, and, like the Constitution, extends those safeguards to all. It provides that "no law shall be enacted in said islands which shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or deny to any person therein the equal protection of the laws." § 5. In the light of the declaration that we have quoted from § 12, it is hard to believe that the United States was ready to declare in the next breath that. . . it meant by "property" only that which had become such by ceremonies of which presumably a large part of the inhabitants never had heard, and that it proposed to treat as public land what they, by native custom and by long association,-one of the profoundest factors in human thought,-regarded as their own.

xxx

It might, perhaps, be proper and sufficient to say that when, as far back as testimony or memory goes, the land has been held by individuals under a claim of private ownership, it will be presumed to have been held in the same way from before the Spanish conquest, and never to have been public land.

Hence, documents of title issued for such lands are not to be considered as a state grant of ownership. They serve as confirmation of property rights already held by persons. They are mere evidence of ownership. The recognition of private rights over properties that have long been held as private is consistent with our constitutional duty to uphold due process.

The state cannot, on the sole basis of the land's "unclear" private character, always successfully oppose applications for registration of titles, especially when the land involved has long been privately held and historically regarded by private persons as their own. (Leonen, J., concurring and dissenting in Republic v. Tan. G.R. No. 199537. February 10, 2016)